Here’s why that matters & why it sustains

The first time I listened to Tom Waits I was stranded at Dublin airport waiting on a bus, hours late, and it had just started to snow – buses started becoming few, then fewer, and hope dwindled as night grew. Desperate for something new in my ears, to distract from the cold, I tried my luck on an album by Tom Waits a friend recommended. There, under a blizzarding sky, I heard that voice singing for the first time, lamenting in a choking splendour of ‘having spent all [his] money in a Mexican whorehouse, across the street from a catholic church’. I was hooked, having never heard something so deplorably uplifting. As an Irish man, it was a warming affront to all those institutions I’d been raised and battered by. This snarling sound, struck harder than any Rancid record I heard previous, (punk being what I thought was the pinnacle of musical, as well as social, dissonance), with a steady flow that punched you in the face periodically – with off-kilter flashes of atonal eccentricities. I started smiling, widely, ’till the harsh cold seemed frivolous, and the snow became beautiful – then, salvation, the bus finally arrived.

I spent most of my early twenties trying desperately at the dawns of dwindling parties to convert revellers to the cause. I used Shore Leave, sung live. Waits ascends into a falsetto at the end that strays from manic to gracious in equal measure. My girlfriend I was with at the time didn’t seem as allured by my new musical obsession, saying he sounded much “like a monster”. She was not altogether wrong, but, I’d argue that’s only when he’s trying to put across the perverse.

The Big Lebowski himself, Jeff Bridges, called Tom Waits the greatest method actor alive, stating Waits has stayed in character since the seventies, which is no small feat.

Like Bowie, Dostoyevski, or Cate Blanchett – Wait’s immediate encapsulation of characters limits our insight into the mind that yields these pieces so neatly from imagination to immortalisation. You don’t know the man, the woman – you know pretence, that which is used to question a deeper truth. What is the soul of man?

It’s this ability that’s most striking in Wait’s writing. In Romeo Is Bleeding, Waits takes on the gravel, chain-smoking screenplay-like prose of a latino gangster who can’t help but fawn for his leader, the cock of the walk, Romeo, who stabs cops for thrills, and smokes, calm as a clam, all the while dying from a gunshot wound he’d never felt, nor noticed, till he just faded away watching Cagney on the cinema screen later that night.

The rasp and cackle, as the boy depicted tells his story – catches you unawares, somehow besotted by the cold, cruelty-inflicting killer, wishing he’d live that much longer, and wishing you’d, yourself, had lived a day at all like it.

Waits sings about lost souls. The downtrodden. Hopeless cases. Carving pieces of existence out of cities, and leaving always too soon, always an Irish goodbye. No character, though, is unaffected, untouched by dreams of betterment.

In Christmas Card From A Hooker in Minneapolis, we’re led through a series of letters through a life of prostitute, who dreams of owning a used car lot, just so she could ride a different one every day, depending on how she feels. Her wit and and her humanity shine through, cutting us cold as the the truth’s lain down in the last lines of the lament – where we realise she’s in a bind, and will probably never see the light of day come Valentine’s day.

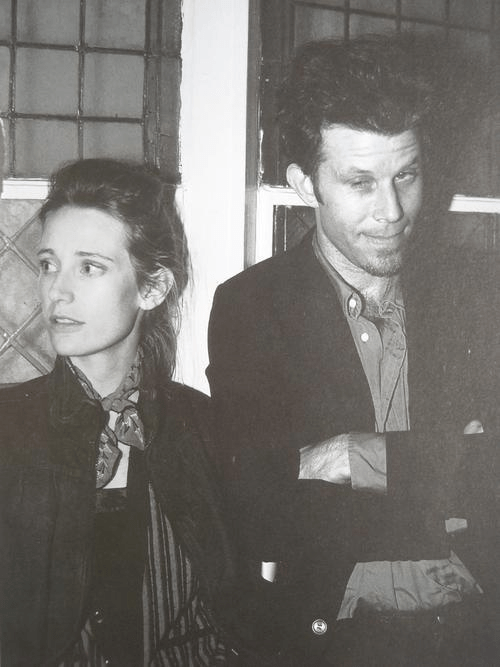

It was with the chance meeting of Waits and Kathleen Brennan, while both working on a Francis Ford Coppola picture, that the second era of Wait’s catalogue, and a vast sea change in music came to bear.

Waits said he didn’t just marry a wife, but a record collection after he and Kathleen were wed. Brennan is who introduced Waits to Captain Beefheart’s oeuvre. It wasn’t for this insight, Waits has been vocal that he’s convinced he would have been a dried-up, has been decades ago. Waits’ yearning lost love songs of before, give way to a rawer strain of delicacy in a song penned especially about Kathleen, Johnsburg, Illinois, one of the most beautiful in Waits’ whole catalogue.

There are few things in music’s history both timeless and exemplar. If musicians aren’t talking about Swordfishtrombones, Rain Dogs and Frank’s Wild Years – Wait’s and Brennan’s trio of albums that started their lifelong musical as well as romantic partnership – than, it’s safe to say, the worms won, or some, altogether less unsightly apocalypse.

Put simply, there’s been nothing like it before or since. It stands alone, strange and bewildering, in its beauty. Some songs sound like a music box, playing for a baby’s cradle in the next room, while others seem to disembowel you and remedy the incision, before any damage is done just in the nick of time.

The thing is about Waits and Brennan, is they don’t cut corners, but cut the fat. There’s a determined emotion in everything they do. That emotion can be anything but ambivalent. It’ll make itself loud and clear. If that then breeds discomfort, that only means it worked.

They’re not here to soothe, through fantasy or illusion. They will present their collective human autopsy as factually as possible. They will portray our innards as they are – warts and all. The aim of the game is to meet them half way, by giving in, and, only then, are you subjected to the greatest warmth that can be garner onto a living thing – assurance you are not suffering in solitude. There are many more of us. Hear our song sung.

The strangest thing is, once you cross the rubicon, you’re shocked by the amount of warm welcoming, love and laughter that greets you. This takes on the guise the spiritual and the homestead in the same breath in Mule Variation’s Come On Up To The House, an album that finally won them a grammy. The essence of Waits and Brennan is to confront the ugliest parts within, and breathe them out – once you do, you’ll find little wounds more than ignorance.

You’ll find a curious love of the unknown. Somewhere within that peculiar there is absolution, a brief respite from fear. A beautiful melody, sung from a battered old hen, that no matter what the odds, or in spite of whatever you’ve done, you should never give up, Never Let Go. Behind the isolation, craven, debauch darkness in Wait’s lyrics, deep within, there’s something yearning, worth airing out. After all, “You’re Innocent When You Dream”.